The Original Cyborg: A Historical Inquiry

Early cyborg experiments were conducted in the pursuit of scientific knowledge

Cyborgs in stories are all over, like in movies and books. But who was the first person in real life to become part machine? To find out, we can look at Kevin Warwick. He got a scar on his left arm because doctors put 100 special things into his nervous system.

This operation in 2002 made Warwick the first cyborg. It combined his body with technology, giving him abilities like those in science fiction. With the implant, he could connect to computers, control robots far away using the internet, and sense sounds like a bat.

Warwick, who is a retired professor of cybernetics from the University of Reading and Coventry University in the U.K., said, “It’s like having a superpower that your brain can control.”

The word “cyborg” was made up in 1960 by a scientist named Manfred Clynes. But stories about cyborg-like beings have been in science fiction since the 1920s. The meaning of “cyborg” can vary depending on where you hear it.

According to Merriam-Webster, a cyborg is a person who has electronic or electromechanical devices in their body to improve their abilities. Early electronic hearing aids were created in the early 1900s, but they don’t make people superhuman. So, it’s debated whether we should call people with hearing aids “bionic.”

The same question comes up for other medical devices like pacemakers. These are implanted to help the heart beat.

Kevin Warwick had his first implant in 1998, a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) chip under his skin. It let computers in his lab know where he was and do things like open doors as he got close.

But he thinks it was the 2002 implant that really made him a “cyborg.” This implant became part of his nervous system and made his body capable of more than regular human biology.

The implant became a part of Warwick’s body as fibrous tissue grew around it, holding it securely in place. The spikes on the implant could sense signals traveling through his nervous system, which a computer connected to the implant could instantly understand.

This computer could also send its own signals into Warwick’s nervous system through spikes. This connection made technology an integral part of Warwick.

This integration gave him new abilities he didn’t have as a regular human. For example, he could control a robot hand in the U.K. from New York City, as if it were his own hand.

When his brain sent a command to his hand to close into a fist, a computer connected to his implant interpreted the signal and sent it through the internet to another computer controlling the robot hand.

The robot hand received the command to close. The robotic hand had sensors that sent signals back through the internet into Warwick’s plugged-in nervous system, which his brain could feel as pulses.

The stronger the hand gripped, the more frequent the pulses, and he said, “I could feel what the hand was feeling.” It was an incredibly powerful sensation.

Warwick conducted various experiments while living with the implant for about three months. He gained a bat-like sense by connecting his implant to a special baseball cap with ultrasonic sensors attached.

These sensors sent pulses into his nervous system, and the frequency of these pulses increased as objects moved closer to him.

One of his most exciting moments was when he connected his nervous system with that of his wife, Irena Warwick, who had electrodes placed in her arm.

Even though he couldn’t see what she was doing, he could feel it when she opened and closed her hand. Just like with the robot arm, he received pulses in his nervous system to signal Irena’s actions.

The Warwicks aren’t the only notable figures in cyborg history. Neil Harbisson made history in 2004 when the U.K. government allowed him to wear his antenna in a passport photo.

This antenna enables him to “hear” colors, and he became the world’s first legally recognised cyborg by a government.

Harbisson, an artist and cyborg advocate, was born with color blindness. His implanted antenna detects colors and converts them into sounds that he can hear, with each color having its own corresponding note.

This remarkable technology, integrated into Harbisson’s skull, even enables him to hear colors that are beyond human vision, like infrared.

Unlike Warwick, who had his 2002 implant removed after his experiments, Harbisson’s antenna is a permanent addition, he’s been wearing since 2004.

However, there’s another definition of a cyborg that requires more than a couple of implants. According to Oxford Reference, a cyborg is a combination of human and machine.

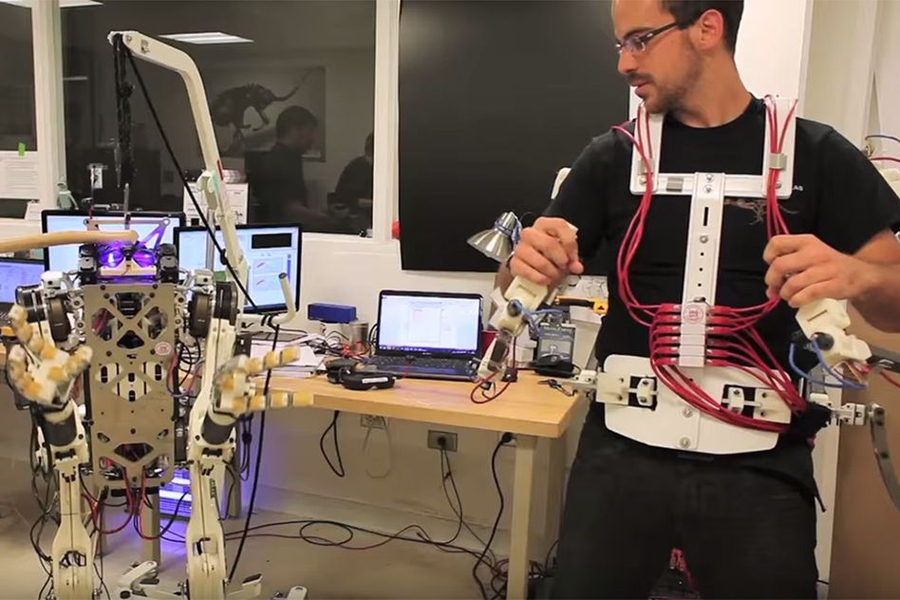

Scientist Peter Scott-Morgan is making significant progress in achieving this by using artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics to combat his motor neuron disease. He has connected his windpipe to an external ventilator for breathing assistance & uses a synthetic voice to engage, similar to Stephen Hawking.

Unlike Hawking, who used cheek movements to operate a computer & select words, Scott-Morgan plans to control through brain-connected implants.

He’s also working on a self-driving robotic exoskeleton stronger than his own body, as shown in the 2020 documentary “Peter: The Human Cyborg.”

Warwick, on the other hand, doesn’t have any disabilities to overcome and has retired from further technological body upgrades. While he doesn’t rule out the possibility of another implant, he’s disappointed with the slow progress in the field of cyborgs since his initial experiments.

According to Warwick, his cyborg experiments didn’t gain much academic traction, and his work was never fully embraced by his peers.

He had expected that by now, many people would have brain implants for direct communication through thought, but this vision has not materialised, which he finds disheartening.

Never miss any important news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Related News

British Investor Who Predicted US Slump Warns of Next Crash

I’m a Death Doula: 4 Reasons I Believe Death Isn’t the End

Tech to Reverse Climate Change & Revive Extinct Species

AI Unlocks the Brain’s Intelligence Pathways

XPENG Unveils Iron Robot with 60 Human-like Joints

Can AI Outsmart Humanity?

11 ChatGPT Prompts to Boost Your Personal Brand

Keir Starmer Hints at Possible Tax Hikes on Asset Income

Navigating the Future of AI: Insights from Eric Schmidt