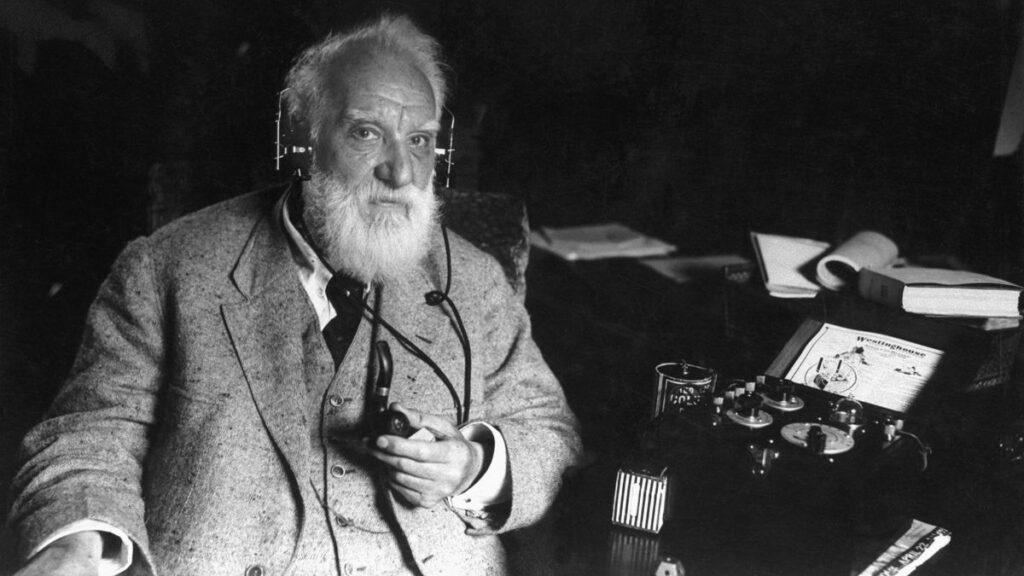

Telephone’s Inventor: Who was it?

Did Alexander Graham Bell really make the telephone, or did he take the idea from someone else?

Phones are very important in most people’s daily lives, but who is considered the genius behind this device? Alexander Graham Bell, who was born in Scotland, is usually given credit for inventing the telephone and being the first to talk on the phone.

In the historic first call on March 10, 1876, he famously said to his assistant Thomas Watson, “Mr. Watson, come here; I want to see you.”

However, according to Iwan Morus in his book “How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon: The Story of the 19th-Century Innovators Who Forged Our Future” (Icon Books, 2022), inventions usually don’t come from just one person.

“Many — I’d almost say all — nineteenth-century electrical inventions were highly contested, with different inventors claiming credit for having solved the key problems first,” Morus explained to Live Science in an email.

“Charles Wheatstone and William Fothergill Cooke, the co-patentees of the first British electromagnetic telegraph, for example, didn’t take long to fall out over which of them really invented it.

Samuel Morse quarreled with pretty much everyone about his claims to inventing the telegraph. And there were similar debates about the lightbulb, and so on.”

Similarly, according to Christopher Beauchamp, a professor of law at Brooklyn Law School, many individuals besides Bell asserted they invented the telephone. Beauchamp wrote in a 2010 article in the journal Technology and Culture that some even suggested “Bell seized the honor fraudulently.”

“It’s not surprising that Bell’s claims were contested,” Morus added. “There was a lot of money, as well as fame, at stake. However, as a historian, I’m less interested in deciding who really invented something, and more interested in how particular individuals emerged from pack to win credit.”

Italian inventor Antonio Meucci, honored by the U.S. House of Representatives in 2002 for his telephone contributions, American engineer Elisha Gray, and German physicist Johann Philipp Reis all played roles in the telephone’s development.

Reis’ 1861 telephone, using a “make-and-break” process, differed from Bell’s. It captured sound, converted it to electrical impulses, transmitted them via wires, and converted them back into sounds. Unlike Bell’s continuous conversation capability, Reis’ device relied on repeated connections and breaks.

Bell’s enduring recognition, according to Beauchamp, is partly due to patent law. In the 1880s, Bell’s legal team, in a significant litigation campaign, secured a “legal monopoly” over the telephone industry. Courts affirmed Bell’s technological claims, granting him extensive rights over electrical speech communication.

Both Bell and Gray submitted telephone-centric patents on Feb. 14, 1876. Although Gray’s arrived first, proactive legal actions led to Bell’s patent being registered on March 7, three days before his famous call with Watson.

Bell’s invention centered on transforming voice-induced vibrations into varying electric currents and converting these variations back into acoustic vibrations reliably, according to Morus. This technological breakthrough set Bell’s device apart from Reis’.

Bell’s ability to craft a compelling narrative also played a role. A year after receiving the patent, his father-in-law organised the Bell Telephone Company, quickly becoming dominant in the US.

Bell’s focus on transmitting vocals, not just written messages, contributed to his legacy. At the time, telegraphy was booming, with inventors, including Bell, competing for more efficient message transmission.

Unlike many competitors, Bell prioritised transmitting the human voice, a choice that resonated with people. Despite debates over the telephone’s inventor, it stands as one of Victorian era’s most influential inventions.

“The key thing about the telephone was the way it brought the electrical future right into the Victorian middle-class home,” Morus emphasised. “It was a vital component in the way the Victorians thought future would be.”

Never miss any important news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Related News

British Investor Who Predicted US Slump Warns of Next Crash

I’m a Death Doula: 4 Reasons I Believe Death Isn’t the End

Tech to Reverse Climate Change & Revive Extinct Species

AI Unlocks the Brain’s Intelligence Pathways

XPENG Unveils Iron Robot with 60 Human-like Joints

Can AI Outsmart Humanity?

11 ChatGPT Prompts to Boost Your Personal Brand

Keir Starmer Hints at Possible Tax Hikes on Asset Income

Navigating the Future of AI: Insights from Eric Schmidt